On a recent afternoon, 67-year-old Saif Islam made his way into the courtyard of a library in Chinguetti, a tiny desert settlement nestled in the Sahara in Mauritania.

Decked in a flowing boubou gown striped in two shades of blue, his steps unsteady but his presence still commanding, he sat on a handwoven mat stroking his grey beard, with his black croc sandals neatly placed to the side.

“It’s these books that gave it this history, this importance,” he said, pointing to a 10th-century Qur’an, its pages brown with age. “Without these old dusty books, Chinguetti would have been forgotten like any other abandoned town.”

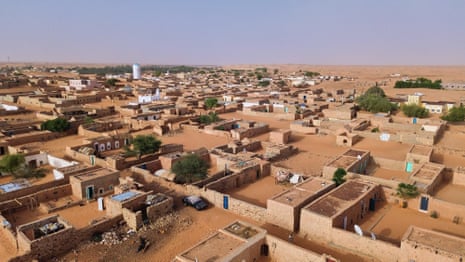

Chinguetti rose to prominence in the 13th century as a type of fortified settlement called a ksar that served as a stopping-off point for caravans plying trans-Saharan trade routes. It then became a gathering place for Maghreb pilgrims on the way to Mecca, and, over time, a centre for Islamic and scientific scholarship, referred to variously as the city of libraries, the Sorbonne of the desert, and the seventh holy city of Islam. Its manuscript libraries played host to scientific and Quranic texts dating from the later middle ages.

For decades, encroaching desert sands have threatened to bury this centuries-old well of knowledge. Residents have left, and tourist numbers have fallen. Most of the current population live in buildings outside the original ksar boundaries.

Islam, the custodian of Al Ahmed Mahmoud Library Foundation, one of only two libraries still open to the public, is fighting to save the manuscripts and drive up interest among his compatriots in the ksar, which was one of the Mauritanian settlements designated a world heritage site by Unesco in 1996.

“Chinguetti is Africa’s spiritual capital,” said Islam, who was born and bred in the town and returned in 2015 when he retired from a job in the civil service in the Mauritanian capital, Nouakchott.

Islam brought out some manuscripts and other artefacts and laid them on the floor. An air cooler stood in one corner, to help against the intense Saharan sun. For weeks or sometimes months, he said, no visitors had come.

“The tourist season is from September or sometimes December to March,” Islam said. “Before, hundreds of tourists came daily. Now, it’s barely 200 per season. After Covid, tourism dropped drastically. The insecurity in Mali affects Mauritania too.”

In total there are 12 family-run red brick libraries still in operation in the town. Together they hold more than 2,000 volumes, including Quranic manuscripts and books on astronomy, mathematics, medicine, poetry, and legal jurisprudence across the Maghreb and west Africa, dating back to the 11th century.

Many were among the valuables brought by traders from across the region. Others reportedly came from Abweir, a nearby settlement that according to oral tradition was founded in AD777 and later fully submerged under sand dunes.

As much as 90% of Mauritania is considered desert or semidesert. Across the Sahel, desertification keeps accelerating. The dunes in Chinguetti are already at the height of the windows of some of the town’s buildings.

Residents say that within living memory there were as many as 30 family-run libraries in the town, but the number has dwindled as people left, particularly during the droughts of the 1960s and 70s. A lack of tourists means little by way of funding for the few that remain. Unesco recognition did not translate into sustained financial support, they said, and promises of funding from public and private entities have gone unfulfilled.

In recent years, the Madrid-based nonprofit Terrachidia, working with Mauritania’s cultural authorities and the Spanish government’s development agency has helped restore several libraries.

The work was done with local builders and materials using traditional building techniques to ensure faithfulness to the town’s centuries-old aesthetic while preserving the treasured manuscripts. A 2024 cultural heritage project brought schoolchildren into ksar for games, classes, and scavenger hunts.

“It was fantastic,” said Mamen Moreno, a Spanish landscape architect who has visited the site and is Terrachidia’s co-founder. “Some children had never been there before although they have always lived in Chinguetti.”

The end goal, she said, was not merely preservation but to attract more resources to generate activity and perhaps even bring people back. “The precariousness of the buildings … has led to overcrowding in the new neighbourhoods, and the ksar is lifeless,” she said. “Cities, like houses, are preserved when they are inhabited.”

Islam agreed. He said he also wanted his compatriots to participate in the race to save the ancient legacies from going under. “Sadly, I see that Europeans are more interested in Chinguetti than Arabs or even Mauritanian officials [but] Chinguetti is in distress,” he said. “It needs everyone.”