The Mediterranean Sea recorded its warmest July on record this year, with sea surface temperatures averaging 26.68°C, according to figures from Mercator Ocean International, which operates the Copernicus Marine Service.

Widespread warming saw 95 per cent of the Mediterranean showing above-average temperatures, and 63 per cent of the basin exceeding the long-term average by at least one degree and 40 per cent by at least two degrees.

The western Mediterranean was the most affected by these identified “extreme anomalies”, according to Mercator Ocean International.

Now, new peer-reviewed research sheds light on just how serious the threat of rising sea temperatures has become in the region. A meta-analysis led by experts at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, and published in Scientific Reports, reviewed 131 scientific studies on the Mediterranean.

Its findings show that even moderate additional warming, just 0.8°C above current levels, could lead to irreversible damage to marine biodiversity, fish populations, and vulnerable coastal habitats.

The Mediterranean is a climate change hotspot

The Mediterranean Sea, like the Baltic Sea or the Black Sea, is a semi-enclosed body of water connected to the global ocean only by the Strait of Gibraltar. As a result, it is warming faster and acidifying more intensely than the open ocean.

Its waters warmed by 1.3°C between 1982 and 2019 – three times faster than the global ocean average. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has identified the Mediterranean as a climate change hotspot.

It is also one of the most important regions in the world when it comes to marine biodiversity and is home to more than 17,000 marine species. Many of these species are only found in the Mediterranean Sea, making it a major biodiversity hotspot.

Warming caused by climate change, alongside other stressors such as overfishing, pollution and habitat destruction, is a major factor threatening marine and coastal habitats in the region.

“The consequences of warming are not only projections for the future, but very real damages we are witnessing now,” said Dr Abed El Rahman Hassoun, biogeochemical oceanographer at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel. Plankton species are already shifting, and toxic algal blooms and bacteria are occurring more frequently.

“The continuing rise in temperatures, sea level and ocean acidification cause severe risks for the environment in and around the Mediterranean Sea.”

No ecosystem is invincible to heat

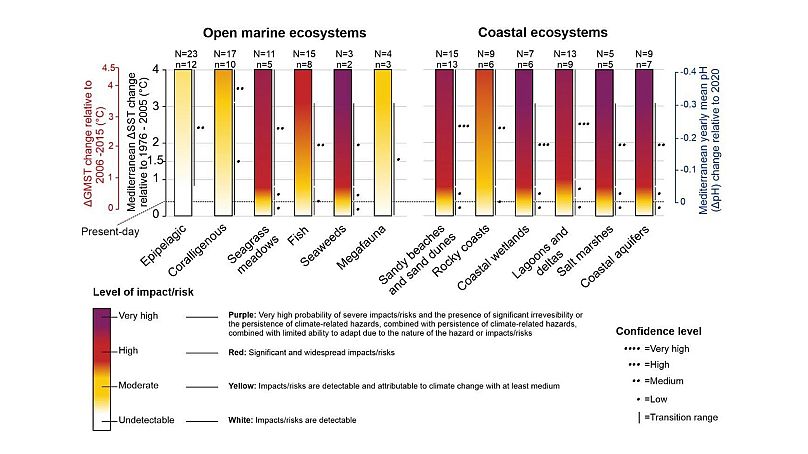

Researchers used the IPCC’s ‘burning ember’ risk framework, a colour-coded visual tool that maps how risks escalate with each degree of warming, to assess threats to Mediterranean marine and coastal ecosystems.

The visual tool shows that even moderate additional warming could bring irreversible damage to the Mediterranean Sea’s ecosystems.

In a world where global warming is limited to between 0.6 and 1.3°C by 2100, seagrass species could disappear completely. Some seaweed species would also decline, while heat-loving algae species could increase.

With 0.8°C of warming, fish stocks could shrink by 30 to 40 per cent, shifting north and making room for invasive species like the lionfish, which threaten biodiversity. Corals are somewhat more resistant than other ecosystems, but if warming rises to 3.1°C, they too are at moderate risk from climate change.

Coastal ecosystems are especially vulnerable due to the combined effect of warming and sea level rise. Coastal erosion threatens the nesting sites of sea turtles, with more than 60 per cent at risk of being lost.

At 0.8°C of warming, this risk increases significantly with sandy beaches and dunes particularly threatened.

“We found that Mediterranean ecosystems are remarkably diverse in how they respond to climate-related stress. Some are more resistant than others, but none are invincible,” says Dr Meryem Mojtahid, professor of paleo-oceanography at the University of Angers and at the Laboratory of Planetology and Geosciences in France.

Mojtahid adds that the study shows even a comparatively small increase in temperature and other climate change-related stressors can have a significant impact.

“Only strict climate protection measures can keep the risks at a level to which ecosystems can still adapt.”